Introduction

Villa Clarín is a settlement of internally displaced persons located in the rural district of Palermo (Sitio Nuevo, Magdalena) Colombia. It emerged as a refuge for families uprooted by violence -especially the massacres that struck rural communities in Sitio Nuevo and Ciénaga in 2000. During their exodus the families sought shelter in nearby towns and in colonization zones such as the buffer strip of Isla de Salamanca National Park, on the right bank of the Clarín Canal, from which the neighborhood takes its name.

Several years later a range of NGOs and the Colombian state offered assorted forms of assistance -food supplies, prefabricated plank housing, and building materials, among others. Public agencies (SENA, CORPAMAG, and others) also tried to launch productive projects in fish farming, poultry, and garment making. Although infrastructure, training, and follow-up were provided for a time, none of the initiatives managed to take root or endure.

This article documents the author’s experience introducing microcredit through the UNIDOS Program (2009), implemented by the Human Talent Consultants Foundation (CTH) in Villa Clarín, and highlights the social factors that limit this strategy’s capacity to overcome extreme poverty. The work constitutes a partial outcome of the author’s doctoral thesis in Economic and Administrative Sciences (Chajín 2016) entitled “Design of a Dialogical Management Model to Facilitate Implementation of the UNIDOS Program in Villa Clarín, Sitio Nuevo-Magdalena (Colombia)” (translated by the author) and draws on earlier microcredit research with the AGAPE foundation (2004).

The study is theoretically grounded in Dialogical Management and the Theory of Development Potentials (Chajín 2010). Methodologically, it adopts a case-study approach and a dialogical form of Participatory Action Research, covering the period 2012-2015.

The decision to test microcredit-together with other development tools-sought to give a boost to small entrepreneurs so they could strengthen economic activities they already knew. The main risk lay in the absence of real, personal, or group collateral; instead, the scheme relied on beneficiaries’ good faith and on their accountability to fellow UNIDOS members for repayment in previously agreed installments.

Loans were financed with a COP 2,000,000 revolving fund donated by CTH to UNIDOS. As borrowers repaid, resources were re-loaned to new applicants. The twelve participating families agreed to charge themselves 2.5 percent monthly interest-well below the rates charged by informal loan sharks (locally known as paga-diario or gota-a-gota, literally “pay-daily” or “drop-by-drop”). Ultimately, the accumulated interest would serve as an emergency health fund for all members.

At the time, Villa Clarín comprised roughly one hundred households, twelve of which belonged to UNIDOS. After two years of weekly work sessions focused on social research and entrepreneurship aimed at escaping extreme poverty, those twelve families were invited to apply for loans of up to COP 500,000 each (≈ USD 174 in October 2015) for investment in activities they already controlled.

Only families that had long participated in UNIDOS received the offer; consequently, they had been trained in the responsible use of money and exposed to microcredit methodologies promoted worldwide by organizations such as Opportunity International and, in Colombia, by AGAPE’s trust-bank model. Because overall group cohesion was fragile and a communal-bank scheme of joint surety was unlikely to work, the participants opted to manage the revolving fund collectively, reinforcing shared responsibility and local ownership of the process.

Theoretical foundation

Speaking of a “Sociology of dejao” immediately summons two reference points. The first is Orlando Fals Borda (1980), founder of professional sociology in Colombia, whose magnum opus La Historia doble de la Costa devotes a full chapter to the figure of the dejao.

The dejao belongs to what Fals Borda called the cultura anfibia -an almost Macondian world where the “cayman man” or “river-turtle man” survives both on water, through fishing, and on land, through farming. He lives by ecological cycles, meeting basic needs without haste or a desire to accumulate capital, enjoying a peasant lifestyle supplied by nature and attuned to celebration and the so-called buen vivir (a locally prized “good-living” ethos).

Parsimonious by temperament, the dejao measures effort and seeks maximum enjoyment from what he already has. Popular vallenato songs such as “La Plata” (Diomedes Díaz) and “La Caja Negra” (Enrique Díaz) capture this outlook: life is to be enjoyed because death is certain; pleasure eclipses long-term planning.

Whether the campesino dejao -the riano who lives along wetlands of the Momposina Depression- or the dejao pushed into coastal cities by violence, the pattern is the same: spend everything earned, live for the moment, adapt rather than transform, and work only to survive. Prior studies with displaced populations had already revealed this pairing of dejadismo and a culture of poverty (Chajín, 2006, 2008).

Introducing the ideas of dejao and amphibian culture into research on Villa Clarín is justified not only by the residents’ rural origins -similar to those documented by Fals Borda- but also by their relocation to a peri-urban setting where they kept doing what they had always done. This heritage situates them squarely among the anfibios and dejaos.

As a subtype of the Sociology of Poverty, the Sociology of dejao moves away from income-based or capability-based explanations. A dejao cannot be treated solely as a victim of the economic system; when offered opportunities, his worldview persists, even outside his former environment of abundance. Rethinking poverty therefore requires grappling with this cultural disposition.

The purpose of this article is to present just one among many cases that reveal what can happen when poverty-alleviation strategies -such as microfinance, banking for the poor, and alternative, cooperative, or community banking- are rolled out. These schemes provide small amounts of capital, and even basic financial-management training, with the intention of breaking the poverty cycle. Yet that cycle is reproduced when beneficiaries spend the day’s entire income and must start over every morning: capital is not accumulated, entrepreneurial capacity is not expanded, and the usual excuse of “low earnings” loses force once the same money is diverted to alcohol or leisure activities.

This article forms part of a broader program entitled “Sociology of dejao”, which blends research and social intervention carried out through Participatory Action Research. Although the qualitative design precludes statistical generalization, the evidence offers useful guidance for social-policy initiatives that seek to strengthen popular economies.

The longstanding belief that poverty stems mainly from low income was challenged by Nobel laureate Amartya Sen (2000), who reframed the debate around human capabilities. A similar line of argument appears in the work of Banerjee and Duflo (2013).

Conventional wisdom equates poverty with unsatisfied human needs that money can readily solve; it also recognizes that, without the skills to manage and invest money, those resources can disappear overnight. The picture grows more complex when we factor in what poor people themselves regard as a good or enjoyable life.

Adherents of the needs-based view assume that anyone presented with a chance to improve living conditions will seize it; consequently, a modest boost such as microcredit seems capable of eradicating much of global poverty. Economist Muhammad Yunus operationalized that promise through the Grameen Bank methodology, whose early success earned him the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize.

Both approaches rest on tacit assumptions. The needs perspective presumes that humans naturally seek happiness and will therefore satisfy their needs-an inference that is not always borne out. The capability approach presumes that people can cultivate talents and skills that let them meet needs and, more importantly, decide which needs to pursue, so that material gain is not always the prime driver. In today’s climate of epistemic integration fostered by dialogical thinking, these views can be joined under what the author calls Development Potentials (Chajín 1996, 2010). From this standpoint, money is necessary but not sufficient for escaping poverty; education, values, entrepreneurial initiative, personal autonomy, beliefs, talents, knowledge, and social relationships are equally critical to genuine human and social development.

Authors Informing the Analytical Approach

Understanding the phenomenon of dejao -conceived here as a culturally learned disposition toward inaction or abandonment when opportunities for change arise-requires a theoretical lens that transcends the traditional dichotomies between structure and agency, individual and society, and economy and culture. For this reason, the study draws on eight complementary perspectives that operate at different analytical levels and illuminate the interplay of subjective meanings, social relations, and structural conditions that sustain poverty in Villa Clarín.

1. George Ritzer’s Integrated Sociology

Ritzer (1993, 2001) argues for a discipline that articulates micro- and macro-dimensions as well as subjective and objective elements. From this vantage point, dejao cannot be explained solely by individual decisions or by structural poverty; it emerges from their interaction. Culturally, people learn to become dejaos; objectively, their occupational world reprises what Fals Borda (1980) called cultura anfibia, rooted in fishing and farming. At the microsocial level, extended-family dynamics mark daily life, while at the macrosocial scale, Colombia’s Caribbean region-particularly the Department of Magdalena-has been shaken by armed conflict, diverse forms of violence, and related political-economic strains.

2. Pierpaolo Donati’s Relational Sociology

Donati (2006, 2011) maintains that social reality is built in relationships rather than in individuals or structures per se; hence, dejao can be interpreted as a weakened relational configuration in which ties drift toward fragmentation, dependence, or isolation. From this viewpoint, social cohesion-and its fluctuating dynamics-can be grasped: for instance, how intense solidarity driven by sheer survival falls to low solidarity once an emergency is past. Such swings have marked the settlement since its founding and during repeated floods when the Magdalena River overflows into the Clarín Canal-displacement forced residents to forge new relationships, yet high cohesion rarely emerged; poverty therefore appears not merely as lack of goods but as relational impoverishment, when the benefits of cooperation and mutual aid fade.

3. Pierre Bourdieu’s Theory of Capitals

Bourdieu (1986) offers tools for understanding how economic, cultural, social, and symbolic capital are unequally distributed and condition access to opportunity. In Villa Clarín the shortage of cultural capital (formal schooling and planning skills), unstable social capital (reliable support networks), and thin symbolic capital (community recognition) blocks the conversion of credit or aid into sustained improvements. Individual capture of collective benefits creates internal intermediaries who divert social support for private gain and weave new power networks inside the group, stalling solidarity-economy projects. Thus, dejao becomes a posture of dependence on both external and internal actors that continually reproduces inclusion-exclusion among members.

4. Miguel Chajín’s Dialogical Sociology

Chajín’s doctoral thesis (2016) proposes a dialogical management model grounded in mutual recognition, active listening, and collective problem-solving. Within this frame, microcredit programs falter not only because of technical flaws but also because genuine communication between outside agencies and beneficiaries is missing. Among economic, political, and cultural variables, the cultural one weighs most: an enduring “emergency mind-set,” tied to humanitarian aid, clashes with UNIDOS’s step-by-step approach of popular education, social-fabric building, administrative skills, and solidarity-organization management-the backbone of Dialogical Management. When representations of development fail to change, many dejaos exploit the advantages of displaying dependence in order to keep receiving sporadic aid from the State or NGOs. This put UNIDOS at odds with the Catholic Church’s assistance-only model in Villa Clarín, which provides help without seeking transformation.

5. Amartya Sen’s Capability Perspective

From Sen’s standpoint (2000), dejao can be interpreted as an expression of capability deprivation rather than of income scarcity. People may obtain micro-credit, yet they do not enjoy the real freedoms or the enabling conditions-education, health, trust, social networks-required to convert that resource into a sustainable improvement in their quality of life. Sen himself stresses: “Poverty can reasonably be identified with capability deprivation” (Sen, 2000, p. 114). This quotation is crucial because it condenses his theoretical proposal: poverty is not reduced to a lack of money but to the impossibility of leading a life that a person has reason to value.

What this way of framing the issue might leave aside is the fact that the micro-credit experiment described here unfolded over more than five years of weekly work under a Participatory Action Research (PAR) methodology. Consequently, the population cannot be fully exonerated for the limited results obtained. A deeply rooted belief persists that the principal driver of social development is money-and, to a lesser extent, education. Nevertheless, successful experiences led by organizations such as Opportunity International and Tearfund highlight the importance of religious beliefs, a dimension that was explicitly incorporated into the Villa Clarín project through the UMOJA (UNIDOS) program.

The religious component of the intervention produced an intriguing contrast. While Catholic-church assistance emphasized social aid and good works, the evangelical Christian perspective adopted by UNIDOS focused on transformation beginning in the spiritual realm-a stance likewise promoted by the AGAPE Foundation in Barranquilla, from which the idea of working on social economy through Christian values was borrowed. In Max Weber’s terms, this echoes the Protestant Ethic (2009). Thus, dejao admits not only an economic and sociocultural reading but also a spiritual or religious interpretation that helps explain why purely financial inputs often fail to generate lasting change.

6. Muhammad Yunus’s Social-Business Model (2010)

In Empresas para todos-published in English as Building Social Business: The New Kind of Capitalism that Serves Humanity’s Most Pressing Needs-Muhammad Yunus sets out a new form of capitalism based on the concept of the social business, an enterprise whose primary purpose is not personal profit-maximization but the resolution of social problems such as poverty, unemployment, and environmental degradation. Drawing on his experience with the Grameen Bank and microcredit, Yunus argues that an economic system focused exclusively on profit has produced deep inequalities and left millions of people excluded. He therefore calls for ethical values to be placed at the very heart of entrepreneurship, promoting sustainable firms that reinvest their earnings in their social mission.

Yunus maintains that every human being possesses entrepreneurial potential and that releasing this capacity can transform economic structures from the bottom up. His proposal thus challenges traditional capitalism and invites a complete rethinking of the role of business as an agent of social justice and human dignity.

The microcredit methodology adopted by AGAPE in Barranquilla-and later replicated on a small scale in Villa Clarín-was inspired directly by Yunus’s work and by UMOJA, the social-economy program promoted by the U.K. organization Tearfund in several African countries.

7. Abhijit Banerjee & Esther Duflo’s Evidence-Based Poverty Studies (2013)

Unlike approaches that attribute poverty chiefly to large-scale structural failures or to irrational decisions, Banerjee and Duflo show that poor people make complex, rational choices amid uncertainty, limited information, and scarce resources. They argue that many aid programs fail because they overlook how the poor actually think and live and therefore call for public policies to be redesigned on the basis of controlled experiments capable of pinpointing effective solutions.

Their micro-economic, pragmatic, evidence-driven perspective challenges received wisdom and promotes interventions tailored to local realities-improvements in health, education, credit, and savings that attack poverty cycles in day-to-day life. Nevertheless, the cultural layer of an intervention-such as dejadismo and the wider amphibian culture-together with the spiritual dimension promoted by Opportunity International and Tearfund, lies beyond the scope of Banerjee and Duflo’s framework. Factoring in elements like individual talents, personal autonomy, and leadership helps explain the psychosocial obstacles that development programs encounter.

8. An Alternative Economy: Manfred Max-Neef, Antonio Elizalde & Martín Hopenhayn (1986)

From Manfred Max-Neef’s Human-Scale Development theory, poverty is not simply a lack of income; it is the non-satisfaction of fundamental human needs-subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation-which are universal but culturally satisfied in different ways. Within this framework, microcredit can be a valid tool only when it boosts synergistic satisfiers that reinforce people’s autonomy, identity, and participation, rather than offering mere pseudo- or inhibitory satisfiers.

Dejao, viewed as inaction or resignation, may be read as the outcome of prolonged frustration of existential and relational needs, while cultura anfibia represents an adaptation straddling two worlds-traditional subsistence based on agriculture and fishing, and a new urban-consumer world-without either world fully meeting those needs. From this perspective, authentic development occurs when people regain the capacity to act as protagonists of their own lives, transforming both their material conditions and their horizon of meaning.

Seen in this light, Human-Scale Development invites us to reconsider the needs that underlie the motivations of Villa Clarín’s inhabitants, who have adopted humanitarian aid as a substitute for the former abundance provided by their natural environment.

The Needs-Centered Approach

The needs-centered approach routinely gives priority to the tangible or traditional indicators of wealth, whereas the capability-based approach places greater value on intangible factors. In the end, both outlooks trace their roots to philosophical conceptions of Being and Having, as discussed by several authors, and they underpin contemporary models of economic growth and of human and social development.

Returning to Yunus’s proposal, it once seemed that he had uncovered the definitive key for eradicating poverty worldwide. Yet the problem is that the advantages of a program are often examined from a single angle-that of the firm or agency that manages the microcredit schemes. Promoters like to repeat that “the poor are good payers,” even though common sense might suggest the opposite. They add that barefoot banking-a label applied to every methodology akin to Yunus’s-offers a humane alternative to usury and to the dangers posed by paga-diario or gota-a-gota moneylenders, the black-market micro-credit that thrives in our context.

On the other hand, the high operating costs of these methodologies-tiny loan sizes, the strategy of taking the bank to the client instead of the client to the bank, constant (often weekly) visits to collect repayments, and the absence of real collateral because borrowers own few assets and mostly work in the informal economy-also make microcredit an alternative to traditional banking, which lends only to those who already have money. For precisely these reasons, micro-lending institutions have multiplied in dozens of countries: it turns out to be a business in which everyone wins-the poor win and the banks win.

Common sense likewise leads us to believe that the more clients a market serves and the more millions of dollars it moves, the clearer the proof that the product is necessary and successful; in this way, microcredit has become an immense business that continues to attract new players. What is not usually done is to look at the business from the client’s point of view, as Banerjee and Duflo (2013) have done.

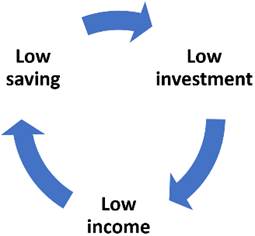

It is therefore essential to evaluate the impact of microcredit on the actual overcoming of poverty. The poverty cycle may be understood as the result of low incomes that prevent sufficient saving to finance a larger investment, which would later raise income (Chajín, 2013). This relationship can be illustrated as follows (Figure 1):

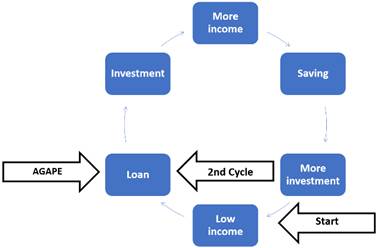

The above can be considered as a circular line of reasoning because poverty ends up being both the cause and the consequence of poverty itself. Microcredit, therefore, was promoted as a “vaccine” against poverty: starting from a low income, a micro-loan would allow someone to make an investment and earn higher income; the additional earnings would qualify that person for more credit, which could be reinvested, and the successive rounds would eventually lift the borrower out of poverty. In this narrative, credit compensates for the absence of savings, which would otherwise impose a brake on investment. A diagillustrate the sequeram to nce would be (Figure 2):

What is taken for granted in this way of seeing poverty alleviation is the belief that as a person improves their income, they will avoid meeting their unsatisfied needs to have more investment capital. Common sense makes us assume that people abstain from satisfying immediate needs to capitalize.

Within this perspective, no inner transformation is required of the economic actor, who appears to carry a built-in “profit chip” or “capitalist chip” that prevents any temptation to spend returns on countless desires. Obviously, a bank or lending institution would not have to make sure of this-unless it wished to be more selective with its clients; in any event, tangible collateral, whether personal or group-based, allows the borrower to obtain several loan cycles as a reward for good performance.

The question is that the above does not seem to occur, in such a way that entire communities are overcoming poverty, despite defenders of these methodologies precisely presenting as indicators of improvement in quality of life that people begin to have more things in their homes, and improve the appearance of their houses.

As long as a person remains caught in the permanent satisfaction of needs -and must work ever harder to do so- he or she will not break free of poverty; in that sense, a large part of the middle class would be in the same situation. The critical point is that need-satisfaction itself becomes the main brake on overcoming poverty, and because the poor inevitably face greater deprivations, rising income does not guarantee a break in the poverty cycle. It hardly seems rational for anyone to sacrifice meeting basic needs if they already have the cash to cover them.

Nevertheless, because there is empirical evidence of improvements in quality-of-life indicators -especially nutrition, health, education, and housing- one might say that the “poverty vaccine” obviously works; yet a knowledge gap remains as to why it works for some and not for others. After all, nobody would endorse a medicine that cures only certain patients.

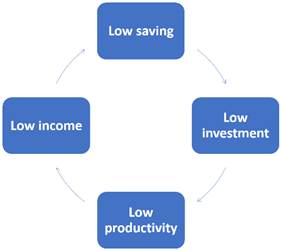

Even if the vaccine works by raising living standards and allowing higher incomes to be saved, that fact alone does not guarantee higher productivity, because the type of business and market opportunities also matter. As Chajín (2004, p. 33) observes, “low productivity leads to low income; this in turn rules out savings, which produces low investment, and that generates low productivity.” (translated by the author) The relationship is illustrated as follows (Figure 3):

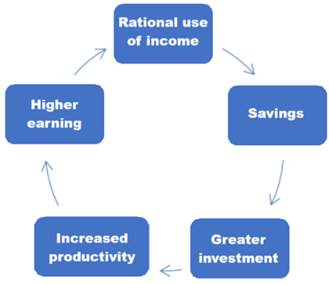

Productivity would be the key and not income and investment to obtain the virtuous circle of overcoming poverty, as improving productivity improves income and with this investment, which in turn improves productivity, which can be illustrated as follows (Figure 4):

Obviously, improving productivity entails a “more rational” use of resources, understood as sacrificing a certain degree of comfort and/or immediate need-satisfaction in favor of a future in which cash flow no longer limits financial growth.

This insight shows that financial resources are a necessary but insufficient condition for escaping poverty: people must also enhance their abilities to manage their living conditions rationally and seize economic-growth opportunities by raising their productivity.

Yet there is a blind spot in the discussion -namely, the subjective and cultural elements tied to the very real sacrifices people must make when they postpone or curb consumption, betting on the future and believing that poverty can be overcome sooner rather than later.

Conversely, when individuals or their cultural environment embrace an immediate-gratification outlook and doubt that overcoming poverty is possible, they are far likelier to remain trapped in it; no rise in income will let them escape that snare. This is the critical point in Villa Clarín, where research evidence confirms the presence of a “culture of dejao” that undercuts any chance of overcoming extreme poverty. It was no accident that a summary of the doctoral thesis, used to motivate UNIDOS members, was distilled into the phrase “Believe that you can so you may achieve what you want.” Hence, the key lies in what people believe, because beliefs motivate their actions.

This implies that microcredit does not work as an escape strategy from poverty except for those families that have shown not only resilience but also a higher level of personal autonomy than the rest of the population. In other words, microcredit works only for clients who have already overcome-or never shared-the “culture of dejao” as Fals Borda understood it in the amphibian lifestyle of the Momposina Depression. Fals Borda perhaps could not foresee what happens when a dejao’s survival depends directly on city life: in that setting, being a dejao becomes a disadvantage that reproduces poverty, precisely what the author’s doctoral research found in Villa Clarín.

Methodology

Strictly speaking, this research cannot be said to have been designed from the outset as grounded-theory work, yet it does contain several of that approach’s components, because both the notion of social entrepreneurship and the administrative theory were shaped during the investigation itself. Consequently, the themes of dejao and amphibian culture began as conceptual touch-stones and later -through an emergent “dialogue” among authors- were consolidated as the core of an incipient grounded theory of dejao within the sociology of poverty.

At the time the field experience took place, Villa Clarín was a neighborhood in the rural district of Palermo made up of about one hundred families, 12 of which belonged to the UNIDOS Program. The micro-credit experiment presented here is embedded in a wide-ranging, multi-year project framed by the author’s doctoral dissertation; the research method was dialogical, and the overall methodology was Participatory Action Research (PAR) from a dialogical perspective.

Within UNIDOS, two years of weekly PAR sessions combined inquiry with social-entrepreneurship activities aimed at escaping extreme poverty. After that period, the 12 UNIDOS families were offered the chance to take out a loan of up to COP 500,000 each (≈ USD 174 in October 2015) to invest in economic activities they already knew. The proposal was extended only to families that had long been active in UNIDOS and had therefore received training on the responsible use of money and on micro-credit methodologies applied in various countries with the support of Opportunity International and, in Colombia, the organization AGAPE, which promotes popular and solidarity-based economy through its so-called trust-bank program. The trust-bank method is related to programs such as Muhammad Yunus’s Grameen Bank (2010); in Villa Clarín, however, those ideas were woven into the UMOJA social-economy program fostered by the UK charity Tearfund.

Because group cohesion was fragile and communal co-signing -typical of village-bank models- would not work, the twelve families agreed to receive a COP 2,000,000 donation as a revolving fund that would grow with the interest rate the group itself set for the micro-loans. They fixed that rate at 2.5 percent per month, far below the rates charged by informal paga-diario or gota-a-gota lenders that fill the banking vacuum in many Colombian marketplaces. The interest fund could eventually be used to cover health emergencies for any of the twelve families.

Each household had to present a business idea and justify it before the others for the loan to be approved; there was no real collateral, only the social pressure that the capital now belonged to the community, although it would be administered by the donor, the Human Talent Consultants Foundation (CTH), under the coordination of researcher-professor Miguel Chajín. If even one family defaulted, the entire group would be affected and no further loans would be granted, even though repayment schedules could be adapted to each venture’s cash flow.

Because only four families submitted proposals, the maximum loan remained COP 500,000. For the purposes of the exercise, borrowers were identified by letters:

Client A proposed buying a multifunction printer (printer-copier-scanner), arguing that she was losing customers with the simpler machine she already had. The researcher helped her price and negotiate a discount for the equipment. She pledged to repay the loan in five monthly installments.

Client B is a farmer who cultivates vegetables on rented or borrowed plots-his lifelong occupation. With more capital he could expand the cultivated area and thereby earn higher profits. Given the production cycle, he proposed a single lump-sum payment after selling two harvests (about five months).

Client C intended to invest in the daily purchase and resale of meat pies, a business she already ran. During her presentation she was asked whether she really needed the full COP 500,000 or a smaller amount; she insisted she could manage the larger sum and committed to five monthly payments.

Client D, also a farmer, had secured the loan of a riverside plot along the Clarín Canal to grow vegetables. He needed to prepare the land and install a simple irrigation system. Neighboring plots were already producing vegetables, so the investment risk was low. He opted for five monthly repayments, supported by other income streams.

The money was disbursed to each borrower during a weekly UNIDOS meeting. The social experiment was intended to be replicated as long as commitments were honored-or at least tangible progress was shown in each enterprise.

AGAPE’s trust-bank process normally starts clients with a small loan and, as they repay, moves them through sisteen consecutive loan cycles, by the end of which they should have accumulated enough capital to operate without AGAPE’s support. UNIDOS adopted that philosophy; the pilot was never conceived as a one-off gesture but as the first step in a social-economy model through which CTH hoped to promote micro-enterprises in poultry, pig and rabbit rearing, fish farming, vegetable production and handicrafts.

Before the loans were granted, CTH had already made several donations to the whole group-hens, pigs, rabbits, seeds and fertilizer for home gardens, plus building materials-and, as a precedent for community work, the members had built and equipped an eco-house for UNIDOS’s weekly meetings. Building home gardens for every UNIDOS household likewise formed part of CTH’s social-development strategy and was expected to provide both motivation and prior experience for tackling extreme poverty.

Thus, within the framework of Participatory Action Research, the methodology wove together the researcher’s prior expertise-he had collaborated with AGAPE for several years-the investigative process in Villa Clarín (supported by sociology students from the University of Atlántico), and the community’s own knowledge, since most residents were peasant farmers; therefore, every project had to fit their occupational profile and sociocultural characteristics.

Stages in the Emergence of Grounded Theory

The application of grounded theory in this study unfolded in three stages:

First stage. A five-year investigation that produced a doctoral dissertation whose purpose was to construct administrative theory from a dialogical perspective by means of Participatory Action Research. During that phase a wide range of authors were considered, and the research was not originally intended to build theory strictly from the data.

Second stage. A conference paper presented at an international administration-research congress of the RIIA network, in which a micro-credit experiment aimed at overcoming extreme poverty was described; a more general version had already been delivered at CLADEA 2013. The paper was later submitted to Revista Dictamen Libre as a research article, and the peer reviewers raised several comments regarding the theoretical framework, which had not been fully developed and therefore needed to be expanded.

Third stage. While addressing the reviewers’ observations for Dictamen Libre, the opportunity arose to employ grounded theory in order to substantiate the initial ideas about the culture of poverty and the dejao character.

On rereading the article to introduce the required adjustments for publication, the author realized that the dissertation itself could serve as a source of information from which to derive the basic ideas, hermeneutic axes, or referents of a grounded theory on the sociology of dejao as one form of the sociology of poverty.

The foregoing contributes to knowledge by showing that grounded theory can be applied to completed research processes-especially those carried out with qualitative methods such as Participatory Action Research. Grounded theory does not necessarily have to begin with a total absence of theory (which may be impossible); rather, new ways of understanding a problem can emerge from a project’s own findings. If the theory that emerges is not confined to the initial theoretical background of a project but instead grows out of the study’s results-and if that new theory advances ideas that go beyond the original framework-then grounded inquiry is an inductive process that meets and converges with deductive research processes.

The dialogical dimension of grounded theory lies in viewing investigation as an open process, receptive to multiple readings even after a project has ended, thus allowing deductive and inductive procedures to converge: the deductive side is the execution of the investigation itself, whereas the inductive side is the rereading of the project prompted by peer critique.

In the present case study, grounded theory therefore traverses three moments of the research project: 1). A completed investigation-qualitative in nature-conducted through PAR; 2). Peer review during the attempt to publish partial findings; and 3). The theoretical re-elaboration of the study. It is in this final stage that the grounded theory truly emerges.

Results

“Client A” paid the five installments on time, including the corresponding interest, and stated that she was already recovering her investment. She was also waiting for the other loans to be settled because she hoped to obtain a new loan to buy a display case and set up a small convenience shop in the front room of her house.

“Client B” repaid the loan in the eighth month; he encountered some difficulties, but he did so punctually and, on his own initiative, also paid the interest.

“Client C” paid four installments and ignored the fifth, which the group did not dare to reclaim.

“Client D” did not pay any installment, arguing that family-health problems had forced him to use the money. He nevertheless made it clear that he did not intend to repay, and the group was likewise unable to approach him to recover the money-even though everyone understood that this would harm them all by eliminating the possibility of new loans and wiping out the health-emergency fund.

Collective benefits from the micro-credit program were evident, because on two occasions the interest accrued was used to meet health emergencies of members who had not taken part in the experiment.

The results did not surprise the researcher-who was also the donor of the funds to the Human Talent Consultants Foundation (CTH)-because a similar experience years earlier with an agricultural collective in the rural district of Los Negritos (El Banco, Magdalena) had ended much the same way. He therefore knew something like this might happen, which underscores the experiential character of participatory research; of course, he never told the UNIDOS group, only the assistant researchers, sociology students from the University of Atlántico.

A large share of the micro-credit problem lies with the client and his or her environment, so the risk is obviously high if those characteristics are ignored. One can even say that repayment capacity in micro-credit is not determined by the contingencies of poverty, such as health problems or bad business. In Client D’s case, it was known that he was indeed a good payer when dealing with paga-diario lenders-probably because of the tacit threats that system entails; in fact, he had once had to sell his house to pay them back. It cannot be expected that the poor will seldom face urgent health situations, but that cannot become an excuse for non-payment. An example is that the only person who fully honored her repayment commitments was Client A, even though during that period her husband suffered a motorcycle accident that left him unable to work for several months.

The evidence confirms that micro-credit has a positive impact when the borrower has already shown himself or herself to be responsible and entrepreneurial, backed by strong solidarity guarantees-conditions that do not prevail in Villa Clarín, a community marked by weak social ties and multiple failed collective-development projects. It may seem unfair that loans are granted to those who have more resources, yet it is also true that the positive impact of micro-credit can be guaranteed only when the borrower is able to manage the funds well. This moral lesson resembles the biblical parable of the talents-a recurrent topic in UNIDOS group meetings.

Given that the article’s title points beyond the immediate case, it is not hard to see that poverty is also self-generated. Without rational use of income and savings, the poverty cycle is never broken; it narrows to a strict income-expenditure-income-expenditure loop with no possibility of saving or investment. No matter how much a poor person earns, if -using a Colombian Caribbean phrase- “he eats it all,” he will remain trapped in poverty. It is no accident that a large segment of the middle class in countries like the United States has fallen into poverty because of consumer society, where the poor are even more likely to enslave themselves voluntarily.

Discussion

The analysis of how each borrower used the loan makes it possible to identify distinct behavioral patterns that transcend individual choice and point to a shared cultural logic. Instead of channeling micro-credit into the consolidation of sustainable productive activities, as the program envisioned, many beneficiaries gave priority to immediate consumption or very short-term outlays -purchasing household items, funding family celebrations, or paying pre-existing debts- without any strategic growth plan.

Far from being explainable only in terms of “economic irrationality” or “financial ignorance,” this conduct reveals a cultural configuration that belongs to what has been called the culture of dejao. Within that logic, present-day survival is privileged over future planning in a setting where historical frustration, the absence of nearby success models, and low expectations of change have eroded people’s sense of agency and life projects.

Access to credit by itself does not transform realities unless it is coupled with human-development training, reinforcement of symbolic capital, and activation of the social fabric. In this case the loan produced no empowering effect; in some instances, it even deepened dependency or disappointment. The evidence therefore suggests that poverty is not merely resource scarcity but also a shortage of subjective and communal structures that enable those resources to become sustainable opportunities.

From a sociological standpoint, the behavior observed here shows that micro-credit policies applied in isolation tend to fail in environments marked by structural exclusion and the erosion of cultural capital. What each person did with the loan cannot be judged solely on technical profitability grounds; it must be read as an expression of a social habitus in which the future is weakened, risk is shunned, and security is sought in what is familiar- even when that familiarity is unproductive.

On the theoretical plane, although the article stems from a doctoral investigation, it actually represents a reopening and continuation of that research at the theoretical and methodological level, giving rise to the ambition of developing a Sociology of Dejao as a branch of the Sociology of Poverty. This has both epistemological and practical implications: scientifically, it confirms that knowledge is always a social construction; practically, it reminds us that a research product is never a finished fact but an ongoing process of knowledge creation.

Conclusions

This study reveals that traditional poverty-reduction strategies such as microcredit face major limitations when they overlook the cultural, subjective, and social elements of the settings in which they are applied. In Villa Clarín, the presence of a culture of dejao -marked by a short-term outlook, resistance to change, and scant social capital- dampened the impact of the micro-credit program even under favorable financial conditions.

The findings show that the success of such strategies depends not only on access to economic resources but also on factors like personal autonomy, the ability to defer immediate gratification, responsible money management, and collective commitment. Far from being a universal remedy, microcredit works only when it is paired with educational, community-building, and relational efforts that strengthen human capabilities and Development Potentials.

As an analytic category, the Sociology of dejao makes it possible to grasp a particular mode of poverty reproduction that stems from culture rather than from sheer material scarcity. This viewpoint urges policymakers and development programs to adopt a dialogical logic that recognizes the subjectivities, lifestyles, and existential meanings of the populations involved. Overcoming poverty, therefore, cannot be understood solely as a technical or financial problem; it is a profoundly human, educational, and cultural challenge.

Structural Components of a Grounded Theory of Dejao

1. Culture of dejao as relational habitus

More than laziness or ignorance, it is a learned disposition shaped by a historically hostile environment of exclusion, paternalism, and institutional distrust.

Dejao functions as a resigned yet functional “way of being in the world,” relying on intermittent aid (Sen, 2000; Donati, 2006; Max-Neef, 1986); interest lies in the present, and effort to build the future is deemed worthless, so present enjoyment compensates for fatalism.

2. Microcredit as a pseudo-satisfier

External credit fails to become productive capital because of scarce prior capabilities, lack of saving discipline, and failure to postpone non-vital needs (Max-Neef, 1986); transformation stalls without integral support and organized solidarity networks.

Instead of empowering the poor, dejao can reinforce internal inequalities and create new forms of dependence (Yunus, 2010; Bourdieu, 1986).

3. Fragmentation of the relational fabric

Loss of solidarity after crises or displacement breeds low cooperation, opportunism, and informal individualism (Donati, 2006, 2011); using scarce resources individually undermines social cohesion.

“Internal intermediaries” emerge, capturing collective benefits for private ends and preventing community building.

4. Amphibian culture and conflict of meanings

People live between two logics-traditional self-sufficiency (fishing-agriculture) and urban consumer dependence-without integrating either one fully.

This ambivalence blocks long-term projection and favors a life in “permanent emergency mode” (Max-Neef, 1986).

5. Capability deprivation as the core of poverty

The inability to exercise agency translates into low autonomy, passivity, lack of future vision, and resistance to structured change (Sen, 1992; Banerjee & Duflo 2013).

A person with agency does not merely await external help but seeks alternatives and reorganizes what is at hand; the dejao, however, becomes a victim of himself and unwittingly reproduces dependence.

6. Dialogue as the pathway to overcoming poverty

The theory suggests that only through authentic dialogical processes (Chajín, 2016)-centered on listening, participation, and collective solution-building, including critical reflection on passive lifestyles-can capacities, talents, values, identity, and social agency be developed.