Introduction

Cultural tourism has become an alternative that allows, on the one hand, to contribute to the economic development of a region or territory and, on the other, to ensure the preservation of traditional manifestations that reflect its idiosyncrasy; in Quindío throughout history, the “Coffee Culture” took root, recognized today as a set of expressions derived from the cultivation of coffee and the fusion of various elements. Although the most representative features of the department are still preserved (Guzmán, Parra, and Tarapuez, 2019), some of them have also been lost over time (Universidad del Quindío, 2016); on the other hand, the different economic, social, and technological phenomena have generated a transition towards multiculturalism, resulting in an amalgamated culture, which despite everything preserves its roots and traditional essence (Muñoz, 2015).

Regarding tourism, thanks to the efforts of various actors, growth has been achieved over the last decades, which has allowed the economy to be energized and employment to be generated. As a result of the initiatives proposed in the Internal Productivity Agenda for Quindío (National Planning Department, 2007), a significant commitment was made to the development of tourism in the region, where different lines with high potential, such as cultural tourism, were identified. On the other hand, with the Declaration of the Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia (PCCC) granted in 2011 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2011), the aim is to value customs, values, and idiosyncrasies; through the document of the National Council of Economic and Social Policy 3803 (CONPES, 2014), the policy aimed at preserving these manifestations in the region was defined.

Likewise, there are other efforts aimed at promoting tourism as a driver of development, such as the Vision and Strategic Plan Quindío 2020 project, the construction and subsequent update of the Regional Competitiveness Plan (Regional Commission for Com- petitiveness and Innovation of Quindío, 2022), as well as the location of the department in the competitiveness ranking, going from a medium-high level to a high level in less than four years (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC, 2013, 2017). Unfortunately, the development of this important line has been incipient for different reasons, among which the absence of institutional leadership and the lack of political will stand out, which translate into a visible disarticulation of the different actors; consequently, a change of conception is required for productive integration (Guzmán, Parra and Tarapuez, 2020) and greater efforts to promote cultural tourism as a driver of development in the department of Quindío.

The objective of this research is to identify the role of strategic actors in cultural tourism in the department of Quindío, which is why, in this study, special emphasis is placed on the recognition of the cultural sector, as well as the strategic actors who have a direct relationship in this area and who, due to their characteristics, could have the capacity to act in a relevant way in this type of tourism.

Although tourism was considered for many years as a simple physical space that ignored the customs built by the people in a territory (Rodríguez, 2010), today it has achieved a dynamic interaction with culture, recognizing the importance of safeguarding and protecting the attractions of an area as part of the heritage territory and as a means for economic development; consequently, nature is beginning to be valued and is susceptible to being protected, conserved, and managed (Campodónico, 2014). From another perspective, Guzmán and García (2010) state that the origin of tourism activity is in culture, particularly in its heritage, and its success will depend on the importance given to these elements for their rescue, conservation, and diffusion.

Tourism has been consolidated as an important socioeconomic factor in countries through local development (Gambarota and Lorda, 2017), and cultural tourism has become a dynamic element of heritage and culture and, in addition, a tool for cultural management and social transformation because it not only guarantees the permanence of values, identity, and traditions but also generates an economic benefit (Ministry of Culture, 2007). According to the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), cultural tourism is the “immersion in natural history, human and cultural heritage, arts and philosophy, and institutions of other countries or regions” (Pastor, 2013:24). For its part, the Mexican Ministry of Tourism defines it as a tourist trip that motivates people to know, understand, and enjoy distinctive features and elements that characterize a society or social group of a specific destination (Sectur, 2015).

Now, cultural tourism seen from an economic perspective is based on local economic development, because it is seen as a dynamic process led in a territory by social actors, who recognize themselves as human groups that come together to defend their interests and act according to the degree of power they can exercise (Mojica, 2005, cited by Chung, 2017), which implies having a certain capacity for strategic action (Scharpf, 1997, cited by García, 2007). According to García (2004), development processes increasingly require the active participation of all socioeconomic agents, who may be directly or indirectly linked, and facilitate the incorporation of innovations in productive and business systems; according to Corona, Zárraga and Ruíz (2015), innovation in the tourism sector arises from the information provided by people and becomes a strategic asset for the generation of value.

Analysis of the interactions

The analysis of the interactions between the different actors from the Triple Helix model establishes a close relationship between the university, industry, and government and becomes a key factor in improving the conditions of innovation in a society based on knowledge (Etzkowitz and Klofsten, 2005); according to Chang (2010), the innovation processes arise as a result of this interaction. For his part, González de la Fe (2009) defines the model as a sociological approach to analyze innovation and guide policies.

In this order of ideas, the academy (university) is essential for the development of scientific and technological innovations due to its formative and investigative nature; the industry develops its economic activity, makes its needs known and proposes alternatives based on its experience; and finally, the government plays a fundamental role in the formal establishment of relations and in the definition of public policies, which must be in accordance with the characteristics of each region (Troitiño, 2002), and these must also be clear and articulated with the private sector and with the communities (García and Vargas, 2016); for its part, UNESCO (2010) states that effective development policies must be in accordance with each cultural context. According to the Ministry of Culture (2013), cultural management must have a comprehensive and multidimensional approach that integrates the actors of the triple helix according to the characteristics of each region, generates synergy, and positions culture as a pillar of development.

From another perspective, the challenges of today's economy have promoted the emergence of cultural clusters as a local development strategy, which have become a new concept regarding the relationships between the cultural and urban spheres, with social interactions taking on special importance (Mommaas, 2004; Lorenzen and Frederiksen, 2007; Kadsson, 2010, cited by Rius and Zarlenga, 2014). For their part, Aldamiz, Aguirre, and Aparicio (2014) state that the cluster provides a network of tacit knowledge to tourism stakeholders. According to Duis (2011), the relationship between tourism and cultural stakeholders enables the integration of populations, their heritage, and their culture. Despite the above, Sanabria (2010) states that the consolidation of cultural tourism structures is complex because it “goes beyond the economic sphere by compromising practices on heritage protection and the intricate relationships that are consequently woven for tourism management” (p. 129), and despite having achieved consensus, there is still evidence of disarticulation between the actors involved, which implies a challenge to integrate both sectors (Confortí, González, and Endere, 2014).

This article is structured as follows: first, there is the introduction, second, the methodology is described, in the third part, the results and discussion are presented, then the conclusions and finally the bibliographical references.

Materials and methods

The research carried out is qualitative and descriptive; in the strict sense, the qualitative approach presents two clearly defined objectives: first, to recognize in the cultural actors, the management inherent to the preservation and promotion of culture and the role they play in the development of cultural tourism in Quindío. The study is descriptive, because there is prior knowledge of the subject to be investigated, variables to be measured are selected, which allow the description of the phenomenon studied; in addition, it is factual and empirical in nature because it involves the use of operations based on objective experience, both in the collection of information and in its analysis and interpretation, in addition to the use of theoretical concepts and schemes.

The research assumes the multidimensional impact of various factors on the characteristics that define the profiles of cultural managers in force in the department; in this regard, practical procedures were specified with the selected population and sample, which were collected by triangulating variables arranged in the information collection instrument. In consideration, the relevance of the mixed research method is established, considering the collection, analysis and linking of qualitative data to have a comprehensive perspective of the object of study.

The research obtained information through surveys and interviews, which included the main aspects related to the strategic actors belonging especially to the cultural sector in Quindío, that is, cultural managers, universities and government entities of the department; for the development of this study, a cultural manager was recognized as a professional who, due to his concern and interest in culture, chooses to dedicate himself to promoting and encouraging, designing and carrying out cultural projects from any field; Likewise, particularities of these actors (University - Company - State) were identified with respect to the management related to the preservation and promotion of culture and the perception they have regarding the potential that cultural tourism represents in the department (see Table 1).

Table 1

Operationalization of variables

To select the sample of cultural managers, the database of the Quindío Culture Secretariat was used, where there was a total of 683 registered managers, of which 559 of them correspond to natural persons and 124 to legal persons, that is, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), obtaining information from 59% and 84% of the sample, respectively; therefore, the database used in the research is of a cross-sectional type and was built according to the object of analysis. Regarding universi- ties, local HEIs that had been in operation for more than 20 years were chosen, for a total of five. Regarding government entities, the departmental secretariats of education and culture were chosen because they have a direct relationship with the research topic.

To establish the number of cultural managers (natural persons) to be surveyed, given the universe identified according to the database of the Quindío Culture Secretariat, the sampling method for finite populations was used. Equation (1)

Z: Level of confidence (95%) = 1.96

p: Positive variability = 0.5

q: Negative variability = 0.5

e: Maximum error allowed = 0.07 Population: 559

To establish the number of NGOs (legal entities), given the universe identified according to the database of the Ministry of Culture of the department of Quindío, the same sampling formula for finite populations was used. Equation (2)

Z: Level of confidence (95%) = 1.96

p: Positive variability = 0.5

q: Negative variability = 0.5

e: Maximum error allowed= 0.07 Population: 124

For the information collection process, a survey was developed to be applied to cultural managers and a semi-structured interview to be carried out at HEIs and government entities; subsequently, field work was carried out, which consisted of visiting each of the cultural actors in the different municipalities of the department of Quindío. The information was collected during 2019. Likewise, for the development of the research, information was also taken from secondary sources such as books, official documents, research, and regulations related to cultural tourism.

The multiple categories of research design based on descriptions based on interviews, narratives, field notes, or written records constitute the qualitative component that involves the characterization of cultural actors in the department of Quindío; in reference to the analysis of the data, the research uses descriptive statistical techniques as the main tool for processing and interpreting the information; the set of data obtained from primary sources was analyzed using quantitative methods; in particular, the statistical program Stata, version 15.0, was used. The techniques used correspond to the use of tools for univariate and bivariate analysis, as well as the study of frequencies or contingency tables.

Results

According to the Triple Helix model (university-business- state), the strategic actors in the cultural sector are cultural managers, HEIs, and local government entities. During the research, relevant aspects of each of the sectors were identified to recognize the role they play in the development of cultural tourism in the department of Quindío.

Cultural managers

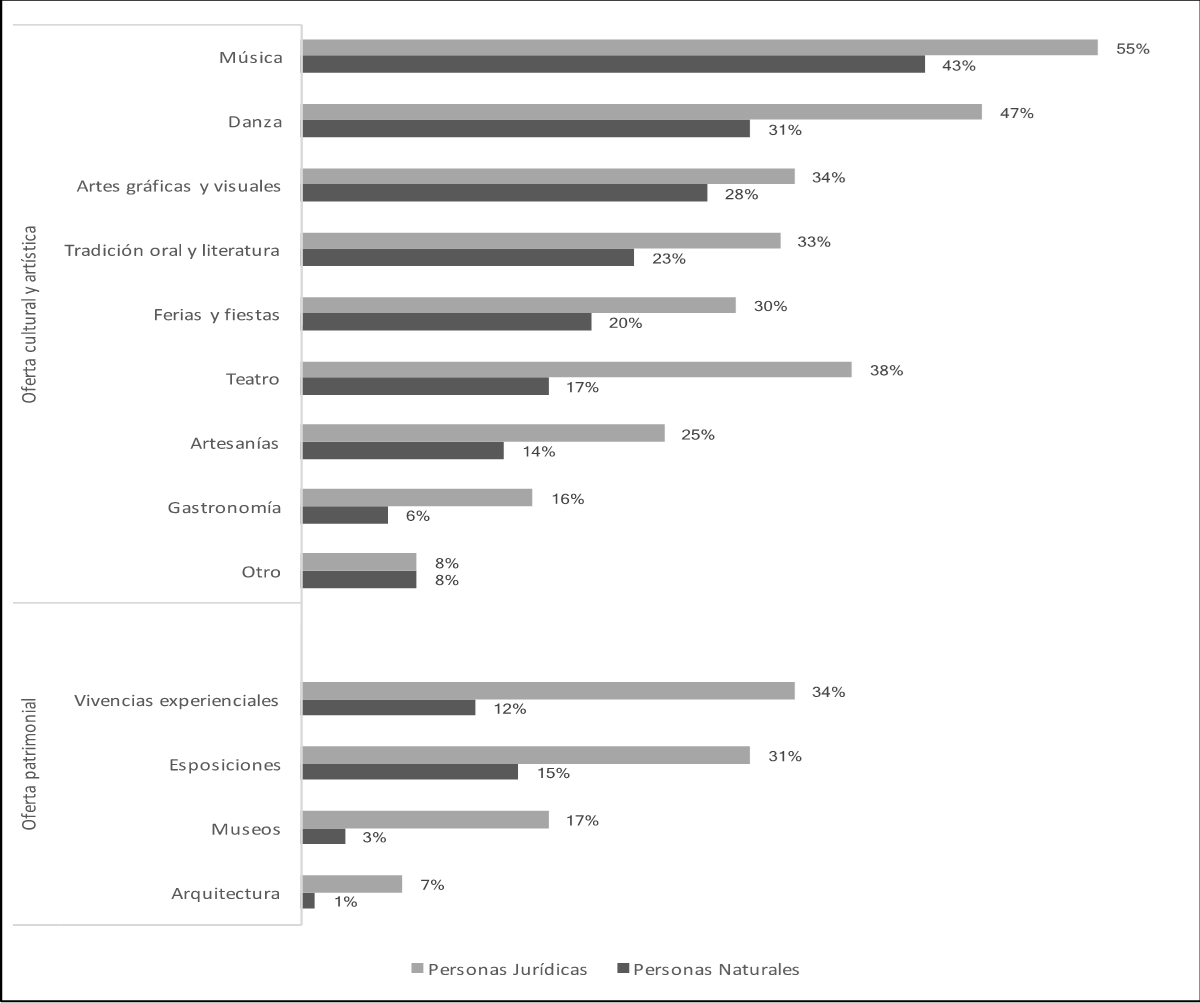

In this study, the cultural manager is recognized as any professional who, regardless of his field of training, has a special interest in culture and is dedicated to its promotion and dissemination, and to designing and carrying out cultural projects from any field; therefore, the cultural managers of the department are classified as natural persons and legal persons (NGOs). Regarding the cultural and artistic offer of the cultural managers, this is broad, represented especially by music and dance; as for the heritage offer, it is a little reduced, but has some representation (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Cultural, artistic and heritage offering of cultural managers. Source: Prepared by the authors

As can be seen, legal entities have a greater cultural, artistic, and heritage offer than natural persons; however, the same trend is maintained, where music has become the most important cultural element in Quindío, followed by dance, graphic and visual arts, and oral tradition and literature. On a smaller scale, there are fairs and festivals, gastronomy, and crafts. However, in the theater there is a marked difference because the offer of legal entities is representative compared to natural persons. Thus, as in the article "Artistic communication model: the development of the performing arts through the empowerment of cultural tourism based on art" (Jaeni, 2023) the results argue that develop culture to create artistic products and tourist spaces based on cultural art to reach a model of communication of the performing arts. Regarding the heritage offer, the experiential experiences and fairs and exhibitions of NGOs stand out, observing a marked difference with respect to natural persons.

It is worth highlighting the high level of education of cultural managers and the relationship that their professional training has with the cultural activity they develop, considering also the handling of one or more languages and their interest in strengthening this type of skill; in this sense, Mariscal (2015) states that in the last decade in Latin America there has been a process of professionalization of the cultural manager, not only in training at the university level but also in its foundation as an academic field of interdisciplinary studies. On the other hand, despite the fact that most have been in this work for more than 10 years, they do not have a commercial registration, which indicates a high rate of informality. In this regard, Mariscal (2015) states that the process of formalizing cultural management has been developing in accordance with new trends, and its importance is recognized as an activity that is inserted in the new dynamics of society, as recognized by the latest governments in Colombia.

On the other hand, in relation to the link between cultural managers and the environment, the great majority establish relationships with external actors, mainly with government entities for the purposes of financing through public calls; however, there is a negative perception regarding the support they receive from the state; secondly, and to a lesser extent, interaction with NGOs is identified for cooperation issues; and finally, with the academy for the development of training programs. Approximately half of the managers are not linked to cultural associations or the community, but they are interested in linking their offer with the tourism sector because they identify great potential around cultural tourism, which is why they propose strategies to achieve articulation. According to Garrido and Hernández (2014), the cultural professional must be an agent that offers a response to the problems and/or demands of citizens, with the ultimate goal of improving their quality of life and well-being.

Higher Education Institutions

The academy as a strategic actor in the Triple Helix model is represented in this study by the HEIs, as they play a fundamental role in promoting culture; for this reason, the Ministry of Culture, through Law 397 of 1997, establishes special incentives and promotes creation, artistic and cultural activity, research, and the strengthening of cultural expressions (Congress of Colombia, 1997). In this sense, Mariscal (2015) states that the academy is concerned with analyzing the various practices of cultural managers and systematizing them to generate knowledge and propose intervention strategies through research projects that contribute to the development of cultural management.

In the department of Quindío, the local HEIs with the longest track record are: Universidad del Quindío, Universidad la Gran Colombia, Universidad Antonio Nariño, Corporación Universitaria Empresarial Alexander Von Humbolt, and the Escuela de Administración y Mercadotecnia University Institution. The cultural offer of the HEIs is wide in cultural credits for the university community (see table 2), highlighting music, dance, graphic and visual arts, and oral and literary tradition (consistent with the offer of cultural managers); these credits are freely chosen by the academic community; it is noteworthy that, during the development of the study, the Antonio Nariño University did not offer cultural credits.

Regarding the link between the HEIs and the cultural sector, agreements were identified with some governmental and non-governmental entities; however, with respect to the tourism sector, the interaction is very limited; in some HEIs, the possibility of making alliances that allow this articulation has been visualized. Faced with the viability of integrating tourism and culture for the development of a productive chain, all HEIs recognize its importance considering that Quindío is touristic by nature; however, some state that this integration depends on the will of the actors.

Table 2

Cultural and artistic offering of the universities of the department of Quindío

The budget of private HEIs for cultural activities comes from their own resources and at the University of Quindío, as a public entity, the Institutional Welfare area must present an annual investment project to the Planning Office.

The IES, within their study plans, have courses for the English language that they offer to students, who must pass the B1 level to obtain their professional degree (Gran Colombia, the School of Administration and Marketing, and Uniquindío to students who entered after institutional accreditation). The University of Quindío offers the Modern Languages program and a diploma in English, and Gran Colombia has a language institute; in the other institutions, English is offered under the credit modality, and in Von Humboldt through an agreement between the Internationalization Office and the Colombo American Institute and the French Alliance, which offers German and Portuguese courses. In the same sense, the majority of the IES offer English courses to the Quindío community; only two universities do not have it as a policy (Antonio Nariño University and Alexander Von Humboldt University). Cultural activities are projected to the community with an offer through solidarity extension (comprehensive training, cultural and sports extension, public training in culture).

The HEIs that have representative groups (Uniquindío and Gran Colombia) make presentations in other educational institutions and in detention centers; for its part, the Antonio Nariño University manages social projects with the Dentistry and Psychology program, which includes a cultural activity with the accompaniment of personnel from the service battalion. As for venues for cultural activities, all HEIs have auditoriums; Uniquindío stands out with five venues and Gran Colombia with four; in addition, all use their sports venues and spaces, such as halls and/or internal patios, to carry out different artistic activities.

Most HEIs are aware of the Policy for the Preservation of the PCCC Conpes Document 3803 of 2014 and develop some programs framed in academic spaces, electives, workshops, seminars, projects or credits at the PCCC. Uniquindío has a course on appreciation of the coffee cultural landscape in the Faculty of Human Sciences and photography in the Visual Arts program.

Government Entities

According to article 305, numeral 6, of the Colombian Political Constitution (Secretary of the Senate, 1991), one of the powers of the governor is to “Promote, in accordance with the general plans and programs, the companies, industries and activities convenient to the cultural, social and economic development of the department that do not correspond to the Nation and the municipalities”; from this perspective, Bernárdez (2003) states that a characteristic of cultural management is that the public sector has a high degree of intervention in matters concerning culture. On the other hand, De Oliveira and De Carvalho (2020) in their study of social participation as an institutional discourse in the tourism agenda of Mexico, conclude that, although the official discourse and policies assert that they aim to respond to the requests and interests of the local community, this is not the case

The main actions carried out by the Secretariats of Culture and Education in relation to the promotion of culture are described below: Firstly, to recognize and strengthen cultural enterprises, the Procultura stamp and calls for incentives and consultation were created by ordinance; in addition, the Ministry of Culture has the Departmental Plan for Cultures-Biocultura 2013-2023, which addresses some aspects related to cultural tourism. Furthermore, Santos, Abreu, Sousa, Carvalho, and Martins (2024) argue that the state can provide specific support and incentives to mitigate the adverse effects of economic cycles, safeguarding the long-term viability of the sector.

In this way, to encourage participation and transparency in the process of calls for tenders, it is important to have accountability from public bodies, as the Brazilian government does in the implementation of accountability in the Brazilian Amazon, which helps the management and good governance of state parks in the Amazon and improves the participation of the actors who interact in these spaces (Da Cunha and Flores, 2023).

The artistic expressions most promoted by government entities are music (orchestras, musical groups, and bands) and folk dance (the most promoted is the “dance of the macheteros”); the Secretariat of Education states that the department should generate its own artisanal products. Considering the importance of the public for the assessment of traditional events, Bernárdez (2003) states that public administration should analyze the socioeconomic profile of the cultural public and thus achieve greater intervention in this type of action. On the other hand, government entities consider that the culture and tourism sectors have not been integrated very well because it is not the result of an elaborate program but of initiatives for the management of resources, which have more of a personal than institutional character. However, there is also an interest in the cultural sector to articulate its offer with tourism, and they also recognize that it is possible to form a productive chain that integrates these sectors despite the fact that a series of difficulties are still evident, such as the lack of leadership and changes in government periods, as well as some challenges such as the formation of human capital and the importance of strengthening cultural enterprises, among others.

Regarding the protection and conservation of the PCCC, the Departmental Secretary of Culture provides guidelines to educational institutions on the orientation of a course with the same name-PCCC. Teachers incorporate it into the area of social sciences and develop it in a transversal manner; according to the Secretariats of Education, Tourism, and Culture, they should be united, which is why there is support for schools with an emphasis on tourism, teacher training, and guidance in the study plans. In this sense, the democratization of access, the guarantee of the valorization of culture, and its preservation for future generations are basic elements for cultural sustainability (De Oliveira, Baracho, and Cantoni, 2024). According to the Policy for the Preservation of the PCCC (Conpes Document 3803 of 2014), it was possible to see the holding of calls for training programs on this subject for cultural managers; however, this was not very well received.

Discussion

The articulation of tourism and culture has become a real challenge, particularly from the Ministry of Culture, it is observed that companies in the tourism sector are not interested in the artistic part; in this sense, Duis (2018) states that these two sectors are separated and poorly articulated for an appropriate management of cultural activities. Despite the difficulty of integration, little by little synergy has been achieved between the Secretariats of Culture and Tourism for the development of artistic activities, the first is in charge of programming and the second of promotion; in this sense, Barbosa (2007) states that the government must support more promotion and training actions for tourism services, making them more relevant and effective to consolidate a value chain. Similarly, according to Boulhosa, Farias and Figueiredo (2021), “the need to reformulate these policies with a view to promoting endogenous development, which considers environmental characteristics and the capacity of local actors to promote their own development” is highlighted (p. 313).

For its part, the Secretary of Education is responsible for ensuring that educational establishments incorporate and generate a transition towards artistic primary schools in curricula and study plans, value them, present goals and projects that promote the program, make the national government give priority to the issue and strengthen a discourse so that the orange economy can attract resources.

Now, analyzing integration from the approach defined in this research also requires the structuring of cultural products; in this sense, Bernárdez (2003) states that public administrations can intervene in aspects such as the creation, distribution, and consumption of the cultural product, as well as in accessibility, price, and promotion. Similarly, Vich (2013) argues that cultural policies must go far beyond the simple organization of events. According to the Ministry of Education, culture should have more interest in being linked to tourism because it enriches the portfolio and makes the destination more interesting; however, other authors affirm that within the field of tourism research, models continue to be replicated where tourism is classified as predatory and trivializing local culture (Moscoso, 2021). In the case of Quindío, culture shapes and has a greater connotation in Quindianidad for the improvement of the quality of life; however, the initiatives generated are more of a personal than institutional nature.

Among the elements of innovation that contribute to cultural tourism from the Secretariats of Culture and Education are the artistic primaries (draft ordinance) and the sponsorship of the cultural offer in tourist events. According to Duis (2018), traditional cultural events and cultural-artistic activities can contribute to innovation through the construction of cultural tourism. For Olko (2017), the innovation ecosystems in a region use the cooperation of different environments under the approach of the Triple Helix model, and it is necessary to analyze how these models fit into the creative and cultural industries.

For their part, the vast majority of cultural managers see a possible link with tourism in a positive light, expressing their interest in incorporating their offer with companies in this sector, especially with hotels, tour operators, and restaurants; the managers identify an opportunity not only to improve economically but to promote and encourage artistic activity and foster cultural identity; likewise, there is interest in having greater interaction with government entities. As for the HEIs, they do not have their offer articulated with tourism proposals or operators in the department; they only participate in cultural events that are brought to the municipalities on anniversary celebrations; in this sense, Sáblíková (2023) shows that local actors are aware of the potential of their destination and support tourism development. However, it is more likely that cultural events are aimed at meeting the needs of residents, not visitors. Most claim that they only carry out internal cultural activities, and when they request a service from another entity, there is negligence. Finally, local government entities consider that it is possible to form a productive chain in cultural tourism with the support of HEIs and cultural managers.

Furthermore, leadership from the state is necessary to consolidate the union of culture and tourism in the territory and consolidate cultural tourism. According to Körössy, Araújo, and Dias (2022), part of the success in destination management depends on the capacity of the different actors to exercise their respective roles and is linked to the decisive figure of a strong coordinating entity, which strives to build a common vision of the destination.

Likewise, this study is of interest to different social actors in the local and national context, mainly those belonging to the tourism sector; on the other hand, the research approach contributes to territorial development; which is why it becomes a valuable contribution for government entities in charge of formulating public policies; likewise, the subject is aimed at academics and scholars in the area, because it is oriented to the design of mechanisms for strengthening cultural tourism in this region.

Conclusions

Cultural managers in the department of Quindío have a representative cultural offer in music, dance, and theater and have an important heritage offer in experiential experiences around coffee culture; the offer of NGOs stands out over natural persons for being broader; their formal nature facilitates their access to financing from the state, unlike natural persons, who are mostly in the informal sector, which becomes a limitation for business strengthening and loss of opportunities. In general terms, cultural managers express interest in starting processes of association with other colleagues and with institutions to incorporate their cultural offer into tourism activity.

From the academy, the most representative HEIs of the department have as an implicit policy in their mission and vision to preserve culture, which is evident in the offer of non-formal education to the academic community and the general population; however, little is visible in training at a professional level. Although the HEIs have representative cultural and artistic groups, these do not have much contact with tourism service providers or government agencies and only participate in the anniversary celebrations of the municipalities by invitation of the mayors, where the public is mainly made up of national and foreign tourists who enjoy the cultural activities.

The government agencies, represented in this study by the Department of Education and Culture, work in a coordinated manner with the artistic primary school program, which is a pioneer at the national level; there is also the Quindianidad chair and the single day institutionalized by the national government, where the additional time is dedicated to the development of the arts; with this, the aim is to educate in culture from primary and secondary school, training the population in the long term in their own cultural manifestations, thus contributing to their protection and preservation.

The strategic actors of the cultural sector agree that Quindío has a series of favorable conditions for the development of cultural tourism, as it is one of the preferred destinations for locals and foreigners; in addition, research has shown the great variety of cultural, artistic, and heritage activities offered mainly by the cultural managers of the department; however, institutional leadership is needed for the formulation of public policies and the materialization of quality and authentic cultural-tourism products, where academia and the state play an important role in creating synergies between the different actors.

The current legal regulations on tourism and culture are based on national guidelines defined in different regulations and official documents; the Declaration of the PCCC by UNESCO has served to promote some ordinances that strengthen culture in tourism activities, however, there is no specific legislation on cultural tourism that supports and promotes this type of tourism as a differentiating factor in the department of Quindío.