Introduction

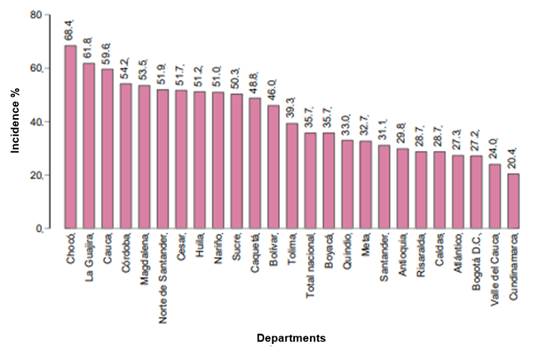

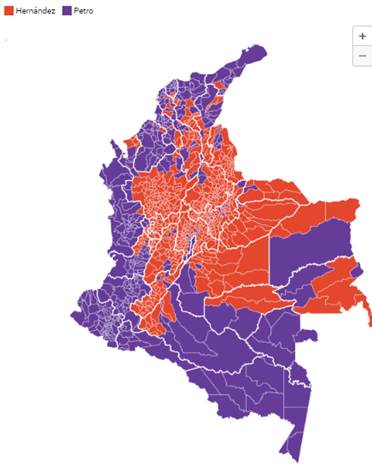

This work was completed in 2018, reviewed, and adjusted in 2022, and is closely related to another study (Chajín, 2018). However, reviewing the data reveals circumstances have not changed much, which serves as a framework for analyzing many of Colombia's problems, such as the resurgence of Antioquia's call for independence (IFM news, 2022-06-26). This work also explores (considering President Gustavo Petro's speech) whether there is a correlation between Petro's share of the votes in the 2022 election to land ownership and poverty, among other exercises, such as linking the U-Sapiens Ranking and other local economic, political, and cultural phenomena. The electoral map published by the "El Espectador" newspaper (2022-06-19), shows a connection between vote distribution and the poverty map.

With Colombia's current political climate and reflections upon the problems documented in structural indices such as GDP, CCI, PI, IDH, and GINI, political scientists and sociologists might ask: Is there any correlation between Petro's vote share in the Colombian Atlantic Coast and the Antioquia, Santander, Risaralda, and Caldas regions, with land exploitation models in those territories? Can these territories' entrepreneurial spirit be related to land distribution and use? Do election results correlate with the productive sector's relevance in those regions? Can election results be linked to the coastal regions' economic weight and development in terms of GDP, competitiveness, human development, and poverty? Was Petro's speech against wealth concentration decisive for electoral wins on the Atlantic Coast? Do Petro's promises carry more political weight in the poorest territories than Rodolfo Hernández's (his electoral opposition) platform of entrepreneurship and anti-corruption in the more developed regions? Does a socialist proposal have fertile grounds in greater poverty contexts, as opposed to entrepreneurship, in regions with better growth and development rates? Delving into these matters can generate many research projects, like the one justifying this work, but it can also shed light on a third option, a mode of production and social system other than Bolivarian socialism or wild capitalism, which are represented by the aforementioned political leaders. Yet more questions remain, and this work may serve as a reference for future research.

The underlying premise is that regional development is linked to political and educational components, as suggested by the U-Sapiens Ranking. Although these aspects cannot be detailed due to the topic's depth, the aim is to construct a strategy integrating economic growth and social development in Colombia. On the subject of land, an article by Rudolf Hommes in "El Tiempo" newspaper on 2013-01-13, discussed farmers' productivity and their significant contribution to Colombia's agricultural production, where Hommes said:

"The study confirms that the most productive farms are the smallest ones. It refers to recent studies estimating that peasant production contributes between 50% and 68% of the total national agricultural production and that 35 percent of Colombian households' food consumption comes from the peasant economy. Considering that the smallest farms, representing 94.2 percent of producers, own only 29.6 percent of the land, they are necessarily more productive than larger land owners, who occupy the remaining 70.4 percent and produce less than 50 percent of the sector's total output" (El Tiempo, 2023-01-13).

Hommes' argument is crucial because not only are small agricultural properties more productive, but the regions where they dominate also have higher economic growth. If we compare the Atlantic Coast with the Central East and West regions in Table 3, with data from over 20 years ago, it reveals these regions have respectively six and five times more small farms than the Colombian Caribbean. These differences are not solely related to land distribution and use but also to other variables, like Gross Domestic Product (GDP), Human Development Index (HDI), Competitiveness Index (CCI), Poverty Index (PI), and wealth distribution index (GINI).

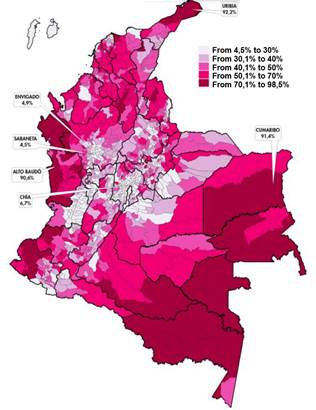

If readers want to consider the validity of this work, they are invited to review Table 8, constructed in 2017, in light of the publication of Semana magazine on 2020-12-21, titled "Poverty in Colombia: these are the most affected regions." According to the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE, by its acronym in Spanish), monetary poverty increased to 35.7% last year. However, some regions saw even higher increases, including Chocó, La Guajira, Cauca, Córdoba, Magdalena, Norte de Santander, Cesar, Huila, Nariño, and Sucre. The information published by the DANE report in 2020-12-21 is summarized in Graph 1.

Graph 1

Monetary poverty (%). Total national and by region 2019. Source: Calculations based on the Integrated Household Survey (2019).

Contrarily, micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises contribute over 80% of Colombia's employment, with just over 50% consisting of micro-enterprises (with fewer than 10 employees). However, their contribution to GDP is just over 6% (Dinero magazine, 2016-09-15). This work analyzes the issue before the health emergency so figures and indices have changed since then, but this work assesses regional inequality in the long term and related trends do not change in short periods.

Interestingly, it is the poor and the middle class, not the rich, who sustain Colombia. For example, remittances from Colombians abroad weigh more in the country's GDP, accounting for 1%, than incomes from coffee exports, even as this aspect is often downplayed to avoid acknowledging Colombian society's significant role in its economic support, as reported by Dinero magazine (REMESAS, 2016-12-12) and reiterated by Leonardo Bonilla (2018).

The inequality in regional development is well-documented and proven, as in Orlando Fals Borda's proposal for territorial reorganization (Fals Borda et al., 1988) and the issue was neutralized in the 1991 Colombian National Constitution, of which Fals Borda was a constituent.

There is a challenge to advance further in the matter, not only from a historical perspective, as studied by Fals Borda in "Historia Doble de la Costa" (2002)), but in terms of addressing the problem through different economic development approaches. Thus, how could actors generate proposals for regional and national development in Colombia, despite the historical limitations of territorial development imbalances?

Objective

To identify a development strategy for Colombia that integrates economic growth and social development, while considering the historical inequalities of Colombian regions, through a mixed and dialogic research approach, allowing for the assessment of regional potential, using the Atlantic Coast, Central East, and West Regions as examples.

Theoretical references

Contextual Background

The Colombian economy requires transformations to advance in its growth and development; noticeably, a large part of its dynamism comes from domestic consumption, especially households, accounting for about 65%. Meaning, that it is the Colombian population who sustains the economy, not the government or large corporations, as is often believed. It is concerning that the financial sector generates nearly 20% of the GDP, which is not associated with production but consumption, as stated in Dinero magazine in a report about the composition of the Colombian economy (Dinero, 2015-09-29). While large entrepreneurs benefit, the rest of the country suffers.

Considering that the largest contribution to the economy comes from households, one could suggest that Colombia‘s economy is poorly managed economically as a country. Furthermore, over 50% of the country's GDP comes from the service sector instead of production, and the agricultural sector, which includes fishing, holds the smallest share, at just over 6%, despite the primary sector as a whole accounting for around 14%. Additionally, agricultural product exports are unimpressive, with coffee, the most important product, not even reaching 1% of GDP. Moreover, Colombia imports nearly 30% of the food it consumes, despite having optimal environmental conditions for becoming a global food production powerhouse. Out of its more than 100 million available hectares, less than 10% is dedicated to agriculture, with just over 30 million used for such purposes, and perhaps the most concerning aspect of this phenomenon is the type of foods imported, commodities such as maize, rice, milk, palm oil, vegetables, and fish, among others, which can be easily produced locally. (El Heraldo, 2016-07-21). Why does the Colombian government sign free trade agreements undermining its productive base?

It does not require much consideration to see how a majority of this 30% of food imports could be supplied by the peasant economy, which contributes more than 50% of national agricultural production, highlighting the need to transform the Colombian agricultural sector. Considering that wealth concentration in the rural sector reaches embarrassing levels globally, approaching 0.9%, making it one of the most unequal situations at 1%. Most vexingly, agricultural production per hectare is ten times more profitable than livestock farming, as acknowledged by Semana magazine (2012).

It is worrisome that Colombia has the highest rate of household indebtedness to the financial sector in Latin America, with over 60% of households affected, the majority for education expenses, accounting for just over 10% of loans, as noted by Carlos Arturo García in El Tiempo newspaper (2014-11-09). If Colombians borrow relatively little for education, it is because they do not believe in the return on their investment, or they are not convinced that education is a worthwhile investment. If we add to this, former President Juan Manuel Santos' poor decision to cut Colciencias' (now the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation or MINCIENCIAS) conjuring a bleak picture of the country's economic future.

Adding to this, Colombia produces commodities, with a significant portion of its exports found in this category. Yet, its economy has failed to transition to agroindustry development, despite the country's comparative advantages in biodiversity and natural resources. Reinforcing the claim of being a poorly managed economy, an issue raised in a 2011 article in El Colombiano newspaper, titled "What does Colombia export? ... eternally commodities," which asked questions related to the manufacturing industry, the agroindustry, and government decisions made over education, science, and technology, still lacking satisfactory answers.

Colombia has its Blue Ocean, as Kin and Mauborgne (2005) said, concerning its natural wealth, but it has yet to recognize it, or in the words of Bernardo Kliksberg (2014), the country is immersed in a paradoxical wealth until it finds its direction in a new mode of development, as suggested by Julio Silva Colmenares (2013). It is unlikely that the ruling elites ignore this estate of affairs, which could be interpreted as a legacy of seeking maximum benefit with minimal effort inherited from the Spanish colonialism. This is what Fals Borda refers to as the "carácter dejao" (derelict attitude) present in the lowlands at the Mompóx region, but which could apply to a large part of Colombia and even Latin America if interpreted in Kliksberg's terms.

Not to mention the relationship between land concentration problems and political violence in the Colombian Caribbean region, as pointed out by José Tapias (2016). This issue motivated Orlando Fals Borda to propose a territorial reorganization in his 1988 book "La Insurgencia de las Provincias" [The Insurgency of the Provinces], supported by local civic, cultural, and political leaders. However, this proposal has barely progressed in over 30 years (Chajín, 2015), even though regional territories can be created following Article 307 of the Colombian political constitution without eliminating administrative regions.

Fundamentally, a large part of Colombia's employment and its families' sustainability depends on the middle class and that President Petro's tax reform could affect this population, which was already hit harder than who by the Covid-19 pandemic.. This is especially concerning given that Petro criticized Congress for not supporting small businesses before becoming president (Petro Gustavo, Twitter, September 23, 2020, 12:46 p.m.) when he defended the middle class. Now, Petro seems on a path to impoverishing this group through a tax reform currently discussed in political circles. Despite this, promoting small-scale agricultural production and agro-industrial development is crucial for the country's economic growth and development, as suggested in a subsequent study (Chajín, 2018).

Epistemological and Disciplinary References

The epistemological reference allowing for the design of an interpretative model for approaching the study of imbalances and potentialities in Colombia's territorial development is a metatheoretical proposal of systems theory, based on Chajín (1996)). This combines Ritzer's integrated sociological approach (1993)) with Bertalanffy's General Systems Theory (1989)) from an epistemological perspective emerging from the way knowledge is generated. In this case, the central categories are Context (Colombia), as the field or territory; Subject, with its codes (the researcher or the micro-sociological entity, or the smallest territorial unit, which is the region, locally dubbed "department," in this case) concerning the Context (Colombia) and the research object (regional imbalances). This work's method is dialogic, where economic growth and social development variables are equally valued to determine the region's potential to generate a development strategy. The object of study reflects the dynamism of territorial entities, and knowledge is the product of the work, consisting of a general development strategy proposal for Colombia, as presented in a similar research (Chajín, 2018). The model is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1

Conceptual references for the meta-theoretical integration of the systemic approach

Aiming to create a regional development strategy or lay its foundations, a systemic model has been chosen to integrate various growth and development indices, such as GDP (Gross Domestic Product), CI, PI (Poverty Index), HDI (Human Development Index), and GINI. The development potentialities approach facilitates articulating variables and building development strategies, envisioning regions as large enterprises; hence, territorial regions as an alternative that Colombia should explore.

Within the potentialities approach, needs are understood as both deficiencies and potentials, highlighting what is lacking or absent along what is wanted or desired. In social theory, development is often understood as fulfilling needs. However, these needs are contextualized for an actor and are simultaneously subjective and objective. First, by satisfying social needs through the HDI, the focus should be on developing regional human talent. If a place's inhabitants do not satisfy their needs, whether because their motivations, beliefs, values, or interests fail at incentivizing this purpose, or because external actors hinder it, we cannot speak of development. Development originates from within, from itself; it can not be imposed.

Capabilities conform to the elements one possesses for fulfilling needs. Having resources does not necessarily imply their exploitation, as is often the case with Colombia's wealth, which benefits foreigners more than nationals; therefore, capacities must consider the context, environment, or territory from which they are perceived and measured, such as an entity's conditions concerning a territory or context to fulfill needs and seize opportunities. Thus, development models and a strategic vision constitute capability. Capabilities concerning competitiveness fall within the purview of regional development planning and require specific knowledge and approaches for building appropriate strategies.

Actions encompass all an entity's activities, efforts, and work to meet its needs. It involves deciding and undertaking capacity development in response to the opportunities presented by context. More concerted actions yield better results. Paralysis or decreases in action, strength, or effort can lead to negatively adapting to a situation or actions getting obstructed by external actors, hindering development. Autonomy levels indicate the development extent of actions. Territory-specific autonomy represents actors' journey between potential capacities and possible and probable actions to meet their needs. For example, resigned attitudes or paradoxical wealth represents conditions of heteronomy in populations facing all the development opportunities offered by their context. The same applies to territorial entities concerning others; for instance, Colombia, as the world's second most biodiverse country, should not find itself on the brink of underdevelopment, as per the ranking established by the author (Chajín, 2018).

Action assessment from the perspective of poverty relates to the population's active efforts to meet their needs in all the forms they employ.

Opportunity represents an entity's context, territory, or environment, which can also include another territory. For example, a region is the context for a municipality, while the country is the region's context. Everything within the macro-sociological, political, economic, and cultural territory constitutes the space for an entity, which can be an individual, a family, a company, or other organizations, up to society as a whole, within the State's general framework. This space is meant to develop capacities and undertake actions to meet their needs. A wealthy environment is much more favorable to entities for embarking on development actions. When actors can develop their capacities to meet their needs, their environment is easier to perceive as providing opportunities. Paradoxical wealth is when individuals demonstrate little autonomy and entrepreneurship despite being surrounded by rich natural environments. However, effort, talent, knowledge, organizational design, and management enable the proper exploitation of opportunities when others in similar conditions remain passive.

Opportunity, as a macro-social component within the Colombian context, is evaluated based on GDP and aims at developing public and private sector organizations for addressing social needs.

Achievement is the measure of need satisfaction, and it occurs when an entity can fully transition from its micro-context to the macro-context, which implies utilizing all of its capacity and developing autonomy for achieving its purposes and goals. In a society where wealth concentration inhibits social mobility and actors' perspectives are passive regarding problem-solving the outcome is poverty.

Achievements in territorial development regarding wealth concentration and regional distribution can be conceived as reflected in satisfaction levels related to social needs, well-being, and quality of life. Table 2 summarizes the theoretical systems approach and the construction of development strategies.

Table 2

Integration of Strategic Approaches

It was presumed that GDP and CCI are linked with economic growth, while HDI and GINI were associated with social development, with PI serving as an intermediary point between growth and development. These variables were also interpreted and associated with the macro variables of development potentialities. Thus, GDP was interpreted as a growth opportunity but not necessarily one for social development.

The Competitiveness Index was associated with a capability for economic growth, but it may not necessarily be linked to a better HDI, especially concerning wealth distribution.

The Poverty Index is associated with the weight of available productive force and can relate to economic growth and social development. It can be equated to an action within the potentialities framework.

The Human Development Index is the starting point for assessing social development as it aims to meet the needs of individuals. Therefore, a higher HDI should be related to better development of human capabilities and poverty reduction.

The GINI index reveals social inequalities as it demonstrates the concentration of wealth. GINI can reflect social development, measuring achievement within the social system. GINI is the point at which growth and development should coincide because economic growth concentrated in the hands of a few is not worthwhile. The proposal is not to take away from those who have more but rather to create an economic, political, and cultural environment that allows all of society to have a dignified quality of life. This requires vertical social mobility, which can be associated with the growth of the middle class. A society can be measured by the size of its middle class, implying that Colombia's GINI whose is at its lowest rating.

A society should not be called "developed" if it concentrates wealth in a way that only the rich and poor exist, even if economic growth indicators are high. However, in a society where the middle class outnumbers the poor without requiring coercive measures (typical of dictatorships), the traditional triangular figure used to show vertical social mobility should be replaced by one shaped like a rhombus. In such a shape, the lower and upper ends are smaller than the middle one, signifying a society where the rich and the poor constitute a minority, enjoying the most well-being and likely having greater social cohesion. An old hypothesis (practically validated) is that violence in Colombia is linked with its shameful GINI index, to which significant corruption of the social system is added.

Methods

This study is a mixed type, combining the description of quantitative data with interpretations from the author's perspective, facilitated by the dialogical method as an integrative mean. It represents research merging deductive and inductive methods, moving from induction to deduction. Although, its starting point is the systemic model and its functional component as potentiality development factors, inductive referents (growth and development indices such as GDP, CCI, PI, GINI, and HDI) are fitted into macro variables such as needs, capabilities, actions, opportunities, and achievements. Results are presented as regional potentialities.

The potentialities development approach serves as an evaluative model for a system's performance. Therefore, it was necessary to integrate indices and manage relevant information for establishing results by region. If the goal is to identify a development strategy for Colombia that integrates economic growth and social development while considering Colombia's regional historical inequalities, a model allowing a regional perspective is needed, which can be placed into regions, using the Atlantic Coast, Central East, and Western areas as examples. The result of this exercise is the creation of a national ranking.

Each territory's weight must be considered equal from the perspective of potentialities and the indices used to determine growth and development, that is to say, it is insubstantial to contemplate the development of a territory with a high GDP and also a high GINI (as in China's case) which falls within the red zone in the ranking proposed by Chajín (2018).

Based on this premise, each variable should carry equal weight when integrated into the model for a comprehensive assessment of regional development.

Regions were grouped by indices, and their positions were recorded to create a general index. Regional information was then divided into three encompassing areas for comparison: Central East, Western, and Atlantic Coast.

Based on a comparison made by Absalón Machado over 20 years ago regarding the number of plots and smallholdings in five Colombian regions, of which three were selected. Indices were compared by encompassing areas, grouping regions within these. 21 out of 32 regions in Colombia were selected for analysis. Seven regions were chosen from the Atlantic Coast (excluding San Andrés for lack of data at the time), six from the Central East area, and eight from the Western area.

Subsequently, regions were grouped into three areas based on GDP, CCI, PI, HDI, and GINI, to verify if regional inequalities regarding smallholdings observed over two decades ago have persisted when using the potential development evaluation model.

A hermeneutic axis for the interpretation of data (as an interpretative hypothesis) is that smaller properties favor economic growth despite inequality and poverty in rural areas. This idea can be linked with other historical works with examples from the Colombian context (such as the Antioquian colonization) concerning territorial mobility, motivations, and impact on territorial development.

This interpretation could support socialist ideas in Colombia unless that should hamper competitiveness. Deficits in competitiveness (which led to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the tearing down of the Berlin Wall) signify that society has ceased innovating and embarking on enterprise. In the Chinese model, where a socialist state engages in the capitalist market, the result is equally undesirable, as seen in Chajín's (2018) development ranking. However, a competitive society with low GINI implies the presence of a middle class that allows society to benefit from its citizens' talents. For instance, Marxist socialism could not be implemented in advanced capitalist countries because of the size of the middle class, which led to the opinion that there was no need to destroy the economic system to build one lacking social mobility. Hence, socialism's real enemy is not the upper class but the middle class. In Marxist terms, this middle class is considered the petite bourgeoisie, comprising the small rural producers and micro-entrepreneurs who drive the economy. As it grows, society becomes more developed.

This interpretation is fundamental for understanding the systemic model adopted in this work. This research goes beyond the creation of a regional development ranking for Colombia, it groups regions into areas to formulate an interpretative hypothesis about other factors related to regional inequality, linking the extent of agricultural property with other indices. Naturally, other variables could be added, such as employment, industrial development, export capacity, and population size, among others. Thus, this work represents an exercise that can continue to evolve. Using widely known indices eliminates the need for additional fieldwork to recognize what has been said for several decades about imbalances in Colombia's territorial development.

The potentiality model enables an analysis for generating development strategies. Table 6 presents various elements for analysis. Indices for each region were averaged to list those with the best results and those with the least favorable ones. Cundinamarca had the highest result, while Chocó had the lowest, followed by La Guajira.

A table was constructed only showing each region's ranking position to facilitate data integration for each index. These results were averaged to rank them from high to low social development, which implies integrating all indices. The ranking was divided into three groups using yellow, blue, and red, with yellow representing the highest social development and red those in a critical state within their context. A rating scale from 1 to 5 was assigned to the best indices, and rectangles were colored green to identify the departments with the highest development for each index.

In a systemic approach, it is assumed that each index should correspond to the others within the same territorial unit. Stating that one territory has the highest GDP and the worst GINI, for example, would demonstrate the possibility of economic growth without social development.

Nevertheless, in line with this study's focus on the imbalances and potentialities of territorial development in Colombia, results must be presented regionally to prove the relationship between observations regarding land concentration issues and compare with other economic growth and social development indices.

Results

Colombia has transitioned from being 70% rural in 1940 to over 70% urban in the first decade of the 21st century. Profound changes have occurred in its economy in 70 years. Although the industrial and service sectors outweigh agriculture, there is a noticeable lack of integration among them, resulting in a significant loss of development potential. For a brief analysis of this aspect, we start with the regional distribution of smallholdings (Table 3).

Table 3

Smallholdings by regions

Differences between smallholding numbers in the Atlantic Coast, Central East, and West areas also coincide with the varying contributions each makes to the country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP), as shown in Table 5.

Table 5

Gross Domestic Product by Regions

[i] Source: Author's work, taking into account data from DANE. 2017-2-1.

There can be a discussion regarding whether an approach to development should assign equal weight to indices such as GDP, CCI, HDI, PI, and GINI. From a dialogical perspective, serving as an epistemological basis for systemic and metatheoretical types, the social and economic aspects should not be reduced to a single factor. This becomes even more critical when some of these factors, when considered individually, can have different interpretations. For instance, GDP is often associated quantitatively with economic growth, while IDH is linked to social development.

The debate surrounding the difference between economic growth and social development finds resolution in the approach to development potentials, given that it integrates all factors or variables. Although the selected indices in this study should not be considered the only ones, they enable a more comprehensive analysis of the situation in each department and region of Colombia.

When aggregating the data from Table 4, an order of importance was established for the regions in their respective indices. The columns display each region's ranking, and adding ranks or horizontally integrating indices shows each's overall rank.

Table 4

Construction of a ranking for territorial development in Colombia

[i] Source: Author's work, 2017. Each color represents a category or development level: yellow for high territorial development and red for low territorial development. The color green highlights the top five ranks' distribution within each level. However, each region's location is decided by its actual weight, determined by the sum of the region's position in each of the indices in the overall table. The higher its weight, the higher its position.

This work's metatheoretical perspective cannot be conclusive because interpreting relationships among data sources related to political topics and the poverty map is not statistically validated. Therefore, this research assumes a mixed character, combining quantitative and qualitative approaches. The outcomes of comparing the selected indices are organized in Table 4.

The GDP's weight by region reveals inequality among them, with the West region doubling that of the Colombian Atlantic Coast and the Central East area tripling it.

These territorial differences are also observed in their competitiveness, with the Central East area with the highest rate, followed by the West, and the Colombian Atlantic Coast ranking last, as shown in Table 6. The territories' Human Development Index (HDI) also reflect the disparities mentioned above, demonstrating a correspondence between the different factors.

Table 6

Regional competitivity index

Regarding poverty, it mirrors the inequality observed in other indices, although the GINI index for the Colombian Atlantic Coast is better compared with the other two areas. It is no coincidence that in the majority of growth and development rankings, regional differences are maintained in a specific order.

Discussion

Everything has a history, and that is why (non sequitur) it is imperative to study it. In this history, we find that large estates have and continue to hinder Colombia's agricultural development and that small farms are more productive than large ones. Better conditions for exports were created thanks to the agricultural development of small-scale production. For coffee, it served as an engine for the country's economic growth via the National Federation of Coffee Growers, created in 1927, which drove the development of its territories. It also exemplifies the economic soundness of cooperation, impacting more than 500,000 Colombian families and ranking among the top 10 largest nonprofit organizations in the world, as described by Jorge Orlando Melo (1996).

Approaching the validity of Table 4's ranking while considering the DANE's graph (2020-12-21), proximity arises between the results and the 2019 monetary poverty graph. However, the model proposed through the potentialities theory analyzes development in five development indices.

This relationship between poverty and the other indices implies examining the difference between growth and development. For instance, the relationship between growth (as measured by GDP size, poverty, and competitiveness) and development (as measured by the Poverty Index, the Human Development Index, and wealth concentration (GINI)). Contrasting GDP with GINI is much more pronounced, as GDP is the quintessential measure of growth, while a lower GINI is closer to development.

However, not only does the DANE's 2019 Integrated Household Survey resemble Table 4's ranking, but this sort of comparison proves valid for other analyses, such as Figures 1 and 2, contrasting the poverty map and the 2022 electoral map. If the regions are grouped by areas, differences in development between them can be noticed, which applies to an integration of the indices from Tables 5, 6, 7, and 8.

Figure 1

Electoral map: from the first to the second round, how Colombians voted. Source: El Espectador newspaper (2022-06-19)

According to Figures 1 and 2, the 2022 electoral map bears some resemblance to the distribution of poverty in Colombia. Therefore, the scope of this research is not to validate what has been said in many ways for decades but rather to propose a strategy to move the country forward by energizing the economy through entrepreneurship in the rural sector for agro-industrial development.

Table 7

Human development index by regions

[i] Source: Author's work, with 2010 data published by Wikiwand. HDI is an index developed by the United Nations that primarily measures life expectancy at birth, education measured by adult literacy rate, combined with education levels and years of schooling, and per capita income in dollars.

Table 8

Poverty Incidence and GINI by Regions

[i] Source: Author's work, compiled from the DANE's data, taken from the Manizales Chamber of Commerce by Caldas (CCMPC), 2014, and poverty and income inequality statistics from the DANE, 2016. The poverty Index (IP) in regional development relates to each region's weight in the other indices. In the GINI index's case, no significant differences were corroborated, although some existed.

Table 9

Development potentialities by regions

[i] Source: Author's work, 2017. Considering the scores from Table 4, in the actual weight and position columns. This table shows that the Central East region has the highest development, followed by the West.

The table above (Table 9) shows that two departments in the Central East region have the top positions in the integration of growth and development indices in the country; however, the West region has more departments in the top positions. Contrarily, the Atlantic Coast area has the most regions with low growth and development indices.

The potentialities result from the sum of the indices held by each region by adding the actual weight of the group of regions that make up each area, divided by the number of departments; the regional average is better for the lower end of the distribution, as it has been grouped in descending order, with one (1) being the top position. Therefore, the region with the greatest potential is the Central East, followed by the West, and the region with the lowest potential is the Colombian Atlantic Coast.

The regional imbalance identified in this study can be validated using other statistics, such as the publication of the U Sapiens 2018-2 Ranking, which categorized the 50 best universities in Colombia from the perspective of their scientific capabilities.

This table (Table 10) shows that the Colombian Atlantic Coast region has three times fewer universities categorized at a high level compared to the Central East region, and twice as few as the West region. This is curiously the same proportion as the differences in their GDPs compared to the total. Additionally, its score is below that of the other regions. In other words, not only does it have fewer universities among the best, but its average score is lower than that of the other regions.

Table 10

Ranking U- Sapiens 2018 by regions in Colombia.

[i] Source: Author, with support from the publication of the RANKING U- SAPIENS 2018-2.

It can be observed that the regional imbalance, in terms of the size of rural properties, corresponds to the social development of the three regions studied in the research. This could be seen as a result in itself when reviewing what has been said about Colombia's "golden triangle," which would be Bogotá, Medellín, and Cali. Antioquia has lost its position to Santander, which prompts reflection on whether Rodolfo Hernández's leadership in the past elections is related to this.

If small rural properties as a percentage of properties allow us to see that the Colombian Atlantic Coast has the fewest, it highlights unproductive large estates. In contrast, the Central East region has the most properties, showing the best results in terms of potential. Consequently, it can be inferred that, given the relationship between small-scale farming and the success of the coffee axis, a strategy for the country's development could be proposed to promote small rural property, as well as micro-enterprises in urban areas, generating a bridge and/or an associative economy based on agro-industrial value chains.

Petro's rise to the presidency can be understood as a response to the popular demand. It cared less about the anti-corruption and entrepreneurship banner of Hernández and focused more on promises that could end up resembling another Venezuela. This is because Colombia's GINI coefficient is 0.53, making it the second most unequal country in Latin America. If this work can serve as a basis for interpreting the results of the past elections, what happened is that most Colombians fear following the path of Bolivarian socialism and the São Paulo Forum less than the intolerable concentration of capital.

Conclusions

The process of economic transformation in Colombia can be based on four dimensions. First, the development of a comprehensive development approach for the country that integrates growth and development. Second, this approach must take into account the significant regional differences and imbalances when comparing the Colombian Atlantic Coast with the Central East and West regions. Third, marked differences also exist within regions, as seen with La Guajira in the Colombian Atlantic Coast and Chocó in the West region. Fourth, one must look at subregions and their municipalities, where marked differences exist between urban and rural areas.

It might be argued that there is no need to consider the agricultural sector as the primary focus of the analysis, given that its contribution is only 6% of the total GDP. However, reference has also been made to the contribution of micro-entrepreneurs, which also represent 6% of GDP. So, if valuing, on the one hand, the contribution of small-scale agricultural production to the country's food security and, on the other hand, the impact on employment of micro-enterprises. Without even considering the contribution of small and medium-sized enterprises to employment and GDP, it could be suggested that the path to Colombia's development lies in small-scale property ownership, or, in other words, its middle class, as a dynamic factor in the economy. Furthermore, complementing the construction of a strategic development approach is the ability to integrate agricultural production and micro-enterprises, especially in agro-industrial activities.

The hypothesis of linking inequalities in terms of land size, even without addressing land use, has arisen. The Colombian Atlantic Coast is predominantly characterized by large, unproductive estates compared to the Central East region, which has more than six times as many rural properties, and the West region, which has five times as many properties as the Colombian Atlantic Coast. It can be seen that small-scale farming is more productive, especially when these figures are placed on the map of Colombia with the indices used in this study.

It would be a coincidence to think that the U-Sapiens 2018 Ranking, for example, corresponds to regional imbalances. Moreover, the electoral results show at a glance that left-wing ideology finds fertile ground among the poorest, while the more prosperous prefer a candidate who represented entrepreneurship, even though his political platform did not focus on closing the extensive wealth gap in Colombia. In other words, with both Presidents, Colombia loses, although it can always get worse with one of them.

It would be a sociological simplification not to relate the recent electoral event to the issue of regional imbalances, which can even be illustrated on a map, as done by El Espectador newspaper (2022-06-19).

Choosing between Petro and Hernández was a political mistake that will be evident in the three periods to come unless an alternative associative approach is considered. This approach would involve building an entrepreneurial network that integrates rural and urban sectors, micro and small enterprises with large and medium-sized ones, capable of articulating the agricultural sector with agro-industrial and service sectors. To achieve this, strategic thinking must be developed, where competition is not the constraint (Salamanca, Uribe & Mendoza, 2017).